Hong Kong, the Coronavirus, the U.S.A, the South China Sea, accusations of Cyber-warfare, Xinjiang, and even racism-the Sino-Australian relations have hit an all time low and these issues have served as the ignition to a long, fruitful, yet inherently uneasy relationship between these two countries. As the new Cold War looms over World Politics, Australia seems to have chosen to stick firmly by the side of Washington.

July 9th, 2020: Australia suspended its extradition agreement with Hong Kong in light of the new National Security Law. In his speech, Prime Minister Scott Morrison further announced plans to extend temporary visas for Hong Kongers in the country by five years, with a pathway to permanent residency. Australia’s travel advice regarding Hong Kong was updated following the new law, advising safety to Australians traveling to Hong Kong by citing risks of being detained and sent to mainland China. While Canberra’s move was not as encompassing as Britain’s decision to open a path to citizenship for as many as three million Hong Kongers, the announcement has provided the latest crack in the deteriorating relations between the two countries. The Chinese Embassy in Canberra immediately denounced Australia’s moves over Hong Kong urging it to stop “meddling in Hong Kong affairs and China’s internal affairs. Otherwise it will lead to nothing but lifting a rock only to hit its own feet.” Zhao Lijian, a spokesman for China’s ministry for Foreign Affairs, emphasised that Australia’s announcement violated the basic norms of international law and relations.

Recently, the Chinese government hit out on Australia’s “undisguised hypocrisy and blatant double standards” over Hong Kong’s new security laws, after the acting immigration minister announced that Hong Kongers would have to go through a national security test in order to gain permanent residency. Chen Hong, the director of the Australian Studies Centre at East China Normal University in Shanghai, analysed the new law saying links with mainland China would play a pivotal role in “sounding the alarm to authorities.” He added by saying, “Australia’s Liberal-National Coalition administration is politicising and recognizing its refugee policy to alienate the people of Hong Kong from the Chinese mainland and to stir up more hostility, instead of promoting stability.” According to him, the Morrison government’s polarizing attitude towards China’s internal affairs would play a pivotal part in pushing the relations between the two nations to disrepair.

The new security law served as the latest catalyst to the steadily simmering relations between the two countries. How did relations turn so sour? Let us turn the dial back to April. China is Australia’s biggest trade partner, accounting for around 30% of its annual exports. China relies on Canberra for iron ore and coal. The wheat and Barley farmers in Australia claim to love the Chinese because they have made them wealthy. Last year, China bought more than half of the 8 million tonnes of the golden grain used in beer and pig feed from Australia. However, beneath this seemingly entrenched economic dependency lie long brewing political differences. In April, the Australian foreign minister Marise Payne called for an independent inquiry into the Chinese government’s response to the Coronavirus in order to trace its origins, independent of the WHO. The Morris government criticised Beijing for its lack of unambiguity in the matter and was the second country to demand for an inquiry, after the United States. A few days before this, Scott Morrision himself claimed that some of the criticism of President Trump in regards to the WHO’s decisions throughout the pandemic were valid. Trump cited Chinese disinformation as a major reason for withdrawing from the WHO, and all these moves did not sit well with the CCP, who claimed that the call for an inquiry is politically motivated.

A few weeks later, Beijing hit back. The CCP announced a 80% tariff on Barley from Australia for the next 5 years. Alongside this, China imposed an import ban on four Australian abattoirs. On May 21st, China announced new rules for iron ore imports which would allow Australian imports- usually worth $41 billion a year- to be set aside for extra bureaucratic checks. In June, China also sentenced an Australian man to death for smuggling in drugs. These measures risk some of the most important sectors of trade between the countries.

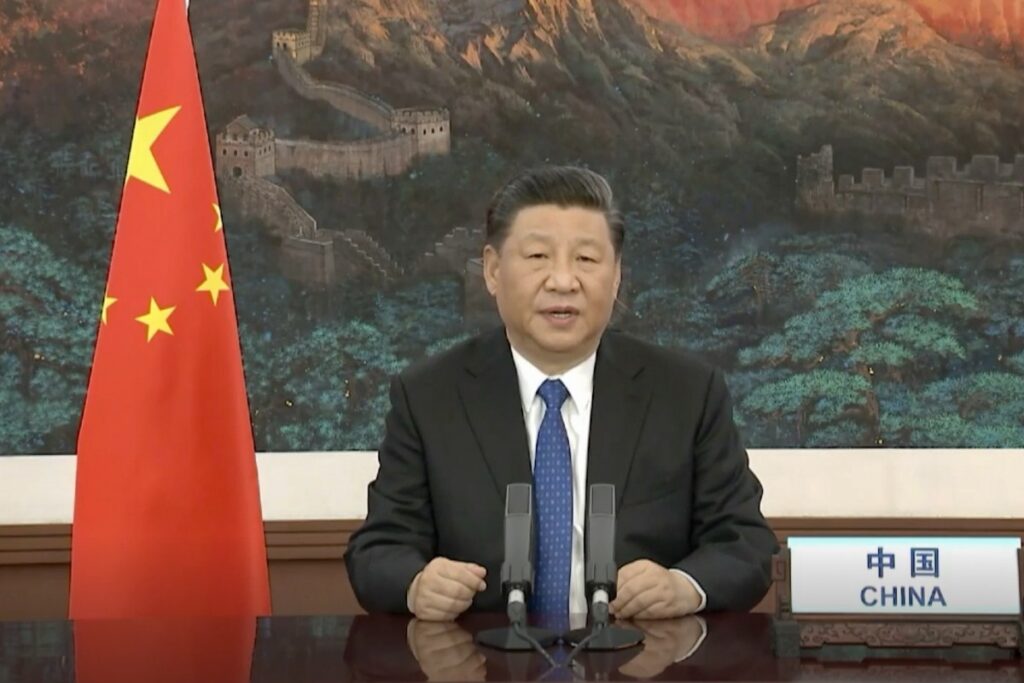

On the 19th of May, during a conference of the World Health Assembly(WHA) at Geneva, China actively participated in the draft resolution which asks for a step wise process of “impartial, independent and comprehensive evaluation of the global COVID-19 response.” President Xi Jingping defended China’s response to the pandemic, claiming China was as transparent and responsive as could be throughout the pandemic. More than 100 countries, including Australia, co-signed the motion. This widespread international support was seen as a vindication for the independent inquiry that was called for earlier. On this, Beijing’s embassy in Canberra issued a statement saying that the inquiry being considered by the WHA was completely different, and one detailed look at the draft would tell as much. This was followed by a rather crude remark where the embassy pointed out that the claim of vindication was “nothing but a joke.”. Trade Minister Simon Birmingham called the embassy’s comment provocative but said Australia would not participate in “cheap politicking” over COVID-19, while many American officials saw this as a sign that Canberra should move away from its reliance on China. This was seen as hypocritical by China, who believes the Australian government has done quite a lot to politically stigmatise the pandemic.

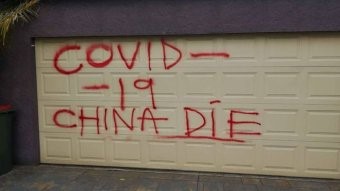

This debacle contributed only partly to the rapidly declining relations. Australia recently announced a complete overhaul of the country’s foreign investment rules which would see the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) having to approve all investments in a sensitive national security business. The government wants the new system in place by January, 2021. While Scott Morrison denied claims of this being linked to the current tensions with China, the Chinese ministry of Culture and Tourism issued an alert the next day, warning of a “significant increase” in racist attacks in Australia and urged people not to travel to the country. While Mr Birmingham has denied such claims, there are indeed countless reports and statistics which show that sinophobic sentiment is on a rapid rise in Australia amidst the pandemic. Chinese authorities updated their travel advice mid-July, alleging that the Australian law enforcement agencies have been “arbitrarily” searching Chinese citizens and seizing their possessions. This was a direct response to Australia’s own warning to its citizens in China claiming they may also be at risk of detention following the new National Security Law in Hong Kong.

To add oil to the fire, the war of words has extended to subtle accusations of cyber-warfare as PM Scott Morrison insisted that a “sophisticated state backed actor” is attacking companies, hospitals, schools and government officials. Security Chiefs and intelligence officials have noted how the hackers use a so-called ‘spear-phishing’ method to steal sensitive login details by sending scam emails, and carrying out regular ‘reconnaissance’ to find weak points in Australia’s defences. China rejected these accusations as ‘baseless‘. The Chinese Foreign ministry spokesman said he believed the claims came from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), which he said was funded by US arms and was making false claims about China .Mr Zhao quite confidently asserted that China is committed to cyber-security, and has itself been on the receiving end of cyber-attacks. In response to this, ASPI director Peter Jennings said the ministry’s comments dodged the contents of the research which were quite extensive and based on sound reasoning. Canberra recently unveiled a $1.35 billion investment to beef up Australia’s cybersecurity capabilities. Chinese media and journalists have echoed previous instances of such allegations- citing in particular the case of Wang Liqiang- and have mocked the hypocrisy of Australian double standards in terms of national security.

The implications of these strains can only be fully comprehended when analysing them within the current international climate. Canberra’s firm allegiance with U.S foreign policy consensus has put it at odds with its strongest trade partner. The relations have always had to walk on a tightrope. Scott Morrison himself has admitted as much, and the fact that no diplomatic tours by an Australian PM to China have been made since 2016 speaks volumes. Ideological differences, and varying political interests have put a limit to the potential of their relations. However, political and ideological differences have only come to the fore in the recent decade, and have only become visible to the public eye in recent months. The pandemic has intensified the tensions between the U.S and China in the Indo-Pacific region, and these tensions have proved quite challenging for Australia. The Pacific is an important point of contention. China looks to emerge Post Covid-19 on strong economic grounds, and would want to tactically manoeuvre its foreign policy interests in this region. The Pacific islands control strategic waterways from the Americas to Asia, which are of vital interest to countries such as Australia and China. The islands have received ample medical supplies by China amidst the pandemic, which has seen its reputation in those areas increase in the process.

China definitely has an interest to access Australia’s strategic mineral and agricultural resources alongside its role as a middle power in the Asia-Pacific region, where China is ambitious to have influence. The economic co-dependency in regards to Iron-Ore persists even now as Beijing tries to recover from the Covid recession. That is a fact which remains undeterred despite Diplomatic brawls. At the same time, however, the Australian Royal Navy’s role in the South China Sea, the banning of Huawei from providing 5G infrastructure in Australia, and the stance of the Morrison government on the Xinjiang issue imply that Australia is not willing to emerge from the Post-Covid world with the same political motivations as Beijing. Whatever is the case, trust between the two countries is at a minimal and the geopolitical struggle will have quite a number of implications especially in the Indo-Pacific region, and will serve a major role in the transformational changes in the international order.[1]