When we think of the deepest warm water port in the world, we don’t expect it to be leased off to foreign merchants for half a century, unless of course the country at hand is the economically stunted republic of Pakistan. Believe it or not, there was a time our state didn’t have to look up to other nations to secure our own interests. If we walk back the ‘path of progress’, we will discover that the port city of Gwadar joined the Federation more than a decade after Jinnah & Co. successfully wrestled an Islamic state from the ruins of British imperialism and Hindu fanaticism.

Gwadar occupies an apex position in the Arabian Sea

But while the Quaid was busy cutting the umbilical cord, his cabinet had little concern for a small fishery lost in the annals of history, and appositely so. In the midst of unfair launching pads, choking refugee crises and the ever present Kashmir Question, developing the Makran Coast could be seen as a somewhat dispensable voice. It was only when President Mirza graced a civil servant turned diplomat turned politician turned foreign minister with the premiership that Gwadar found itself suddenly at the center of the Cold War.

Historically, the land belonged to the Khanate of Kalat, the masters of modern-day Balochistan. But owing to political unrest in the Sultanate of Oman, the area that is now Gwadar was granted to the Omani royal Sultan bin Ahmad with the understanding that it would be returned later on while he waged civil war against his brother. Following his victory, he returned to Muscat, but maintained sovereignty over Gwadar through a wali (governor). Although Omani rule continued with the new Sultan ordering his wali to add the nearby Chabahar port (now in Iran), Balochi resistance continued with skirmishes, raids and counter-raids until the advent of the British. In fact, the Omanis constructed three forts to defend against engagements with local Baloch tribesmen.

But while the Brits had suffered terribly at the hands of the Afghanis, the humiliation they had received at Kabul turned into an overcompensating desire to restore the English name. Charles Napier sinned and his administrators realized the economic potential of the Makran Coast and sought to intervene in the Baloch-Omani dispute, being the responsible older brother Britons have always seen themselves as.

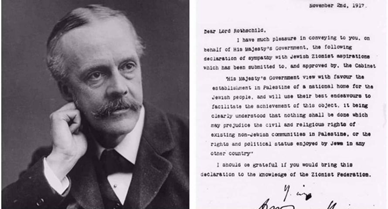

The Palestinians would agree with me when I say that the British have this annoying habit of promising things they don’t own to people they don’t care about. Confirming trading rights with the Sultan, the British told the Khanate to go home with the claim that Gwadar had been granted to the Sultan indefinitely and so the Khan had no right to it. Following partition, some of these trading rights were transferred to New Delhi as the Sultan fancied himself a fine neighbour.

This is when matters took a turn south as the Makran Coast acceded to Pakistan but Gwadar didn’t. Reza Shah of Iran was sniffing around too, with the hopes of merger with the Chabahar port. He was backed by the CIA which was aiming to secure a strategic foothold at the junction of the Middle East, Central Asia and South-East Asia before it fell to the Soviets.

When Karachi engaged with the US Geological Survey on the Makran Coast led by Surveyor Worth Condrick, Gwadar was identified as a suitable site for a seaport. With Pakistan still being a dominion, the pressure mounted on the Queen’s government. The American lobby insisted on Irani rights to it as the Shah was known to be strongly anti-Soviet. Pakistan wanted it to secure its frontiers while Oman wanted it for itself. In the midst of this crisis, PM Noon realized its future economic potential as well as its vitality to Pakistan’s security; he called Gwadar the dangerous back door that was an omnipresent threat to Pakistan’s existence unless it was taken over. He handed over the task of convincing the British to let Pakistan have the port city to his wife, Begum Viqar un Nisa.

Mr and Mrs Noon on a visit to New Delhi with PM Nehru

An Austrian by birth, she had met Noon at Oxford, converted to Islam and accompanied him to Pakistan. Now she flew to Westminster in order to convince the Parliamentarians to allow Pakistan to take over. Reportedly, She even went to Winston Churchill, a champion in making ‘Pakistan’ who lobbied too for ‘ Gwadar port’ to be given to Pakistan. In conformity with the Quaid’s preference of the pen over the sword, the Miss Nisa successfully convinced Britain to let go of one of its last remnants in the subcontinent after two years.

Then came the task of convincing Oman to follow suit. Supposedly, the Sultan first offered it to India (so much for Pak-Arab friendship) which promptly turned it down and then to Iran but it was impossible for the Shah to govern it without Pakistani assistance and a snubbing wouldn’t have left Karachi too sympathetic to Tehran. Pakistan was also home to a majority of Omani foreign workers before the oil rush of the mid to late twentieth century.

Once Sultan Syed bin Taimur agreed to hand over the city, another disagreement evolved into a 6-month deadlock. PM Noon had assumed the transfer of Gwadar would take place in accordance with the incomplete agreement between the Sultan and the Khan of Kalat. The Sultan, however, expected to be financially compensated. His sultanate was deeply in debt and he needed funds to act against his opponent Imam.

On the request of the Pakistani government, the Ismaili leader Prince Agha Khan IV purchased Gwadar for a sum of Rs 5.5 billion (US$ 3.89 billion in 2019), gifting it to Pakistan. Some optimist economists claim this to be the biggest steal since the American purchase of Alaska from Russia back in 1867. On December 8, 1958, the navy light cruiser ‘Babur’ sailed to Gwadar under Commodore M. Asif Alavi to confirm the admittance of Gwadar into the Federation.

But the real commendations lay at the door of the Noon household. If it weren’t for PM Feroz Noon’s timely and pivotal decision to go through with the purchase, or Begum Viqar un Nisa’s intelligent charm and diplomacy, Gwadar would have never been a part of this country in all likeliness. Pakistan may not have spent the last two decades patting itself on the back for its golden hen, CPEC certainly wouldn’t have existed and local authorities wouldn’t be allowing foreign traders to take up 91% of what their land granted them. Surely, the Makran Coast would have been as much of a de facto persona non grata as non-CPEC parts are.

Sadly, very few people today understand the magnitude of the work the founding fathers did and in what circumstances and why. If we change our focus from cheap, sexist entertainment towards realizing our history, perhaps we might witness another Feroz Khan Noon and another Viqar un Nisa Begum, whose efforts would bear fruits to generations half a century later.